by Father Jim Warnock

We have just returned from ten days in Ireland, split between Dublin, Belfast and Londonderry. It was interesting to me in part because I had been there in 1977 in the midst of the Troubles. In those days, I was working for Jews for Jesus. The story was that a Catholic bishop, asked when there would be peace in Northern Ireland, replied that it would happen when the Jews came preaching Christ. Well, they came, and I was driving the van for one of the music groups.

The Troubles were very much in evidence in 1977. The British Army patrolled the streets, heavily armed. While driving, an army truck would pull in ahead of you, and soldiers would point rifles at you from the back. Two bombs went off while we were there, and peace didn’t come.

The Troubles ended in 1998 with the Good Friday Agreement, and I was anxious to see the changes that had ensued. It wasn’t all that I had anticipated. We took the standard bus tour through Belfast which drove past the Catholic housing in Falls Road and the Protestant Shankill. The driver pointed out the very explicit murals by both Protestants and Catholics that memorialize the Troubles and their community’s role in them.

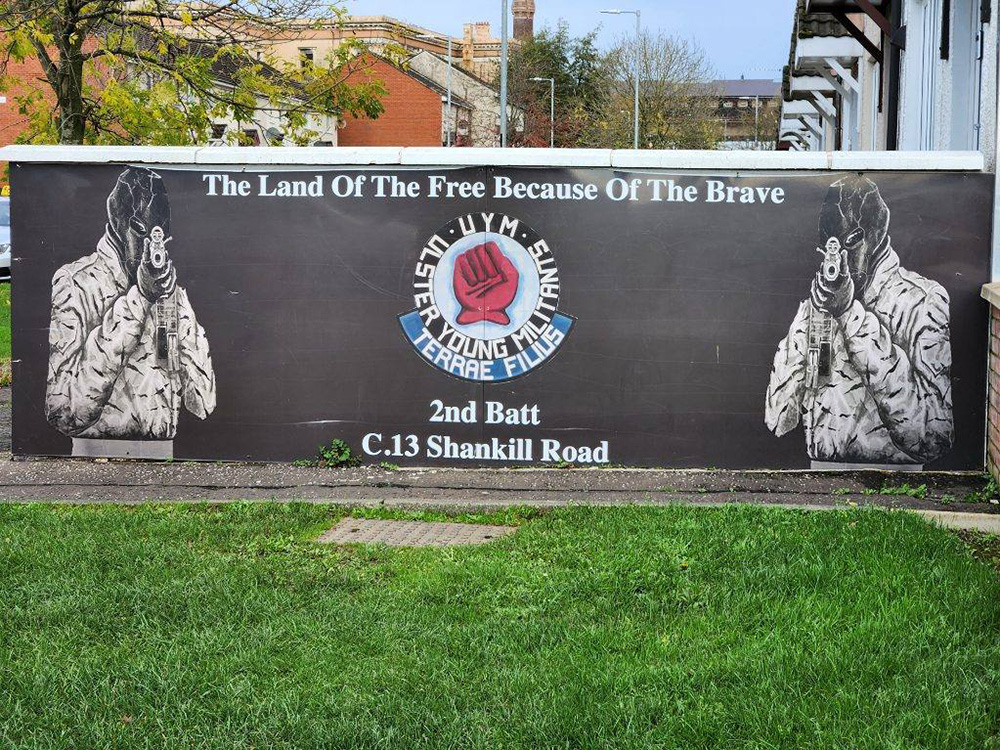

The next day we took a Black Taxi tour through Belfast. These are taxis driven by men who lived through the Troubles. They take you into the neighborhoods, explain in detail what happened, how it’s remembered and what impact it continues to have today. We went into Shankill and were immediately confronted by a mural of Stephen McKeag, the most effective killer of Catholics during the Troubles. Next to him is a mural of masked men under the banner of the Ulster Young Militants pointing assault rifles at anyone entering the community. These murals are designed so that McKeag’s eyes and the muzzles of the guns follow you as you walk past. It’s an intimidating message.

The wolf shall live with the lamb, the leopard shall lie down with the kid, the calf and the lion and the fatling together, and a child shall lead them. — Isaiah 11:6

The Catholic murals in Falls Road are kinder, emphasizing links with oppressed peoples and occasionally portraying innocents killed in the fighting. They depict the faces of the prisoners who died while on hunger strikes to protest their imprisonment. I found myself with more sympathies for the Catholics, but their walls also portray IRA violence as a good and noble thing.

This could be depressing, and I found it so at first. Thinking about it though, I realize that, as John’s Gospel tells us, the light really does penetrate the darkness. The peace treaty, signed in 1998, endures because life without violence is better. The murals depict a hatred which still exists, but it’s being overcome by the realization that it’s better to turn away from anger, to love God and as a consequence begin to love your neighbor, to begin to see the common humanity we all share. The peace that currently exists in Northern Ireland isn’t a finished process, but it’s a step on the way.

The light does penetrate the darkness, it seems. Our Black Taxi driver was shot five times during the Troubles. He is thrilled that it’s over, that his teenage daughter lives in a society without bombings and can plan to attend college to study accountancy. He says it will take generations before the walls can finally come down, and I believe that. Reconciliation is a process. People have to work at it, to continue to resist anger and fear, to turn toward, in the case of Protestants and Catholics, a Gospel of love that will break down barriers of hostility and renew our lives.

It’s Advent season, the time when we remember Jesus’ birth and anticipate his return. We see a lot of trouble and violence in our world. Northern Ireland reminds me that violence isn’t the end, that peace is possible, that the Gospel gives us answers in the person of Jesus who taught us the essentials of loving God and loving our neighbors. Let’s pray that Advent will be a season of peace for us, that we can have a testimony of God’s love in our neighborhood as we head into 2023.