by Father Jim Warnock

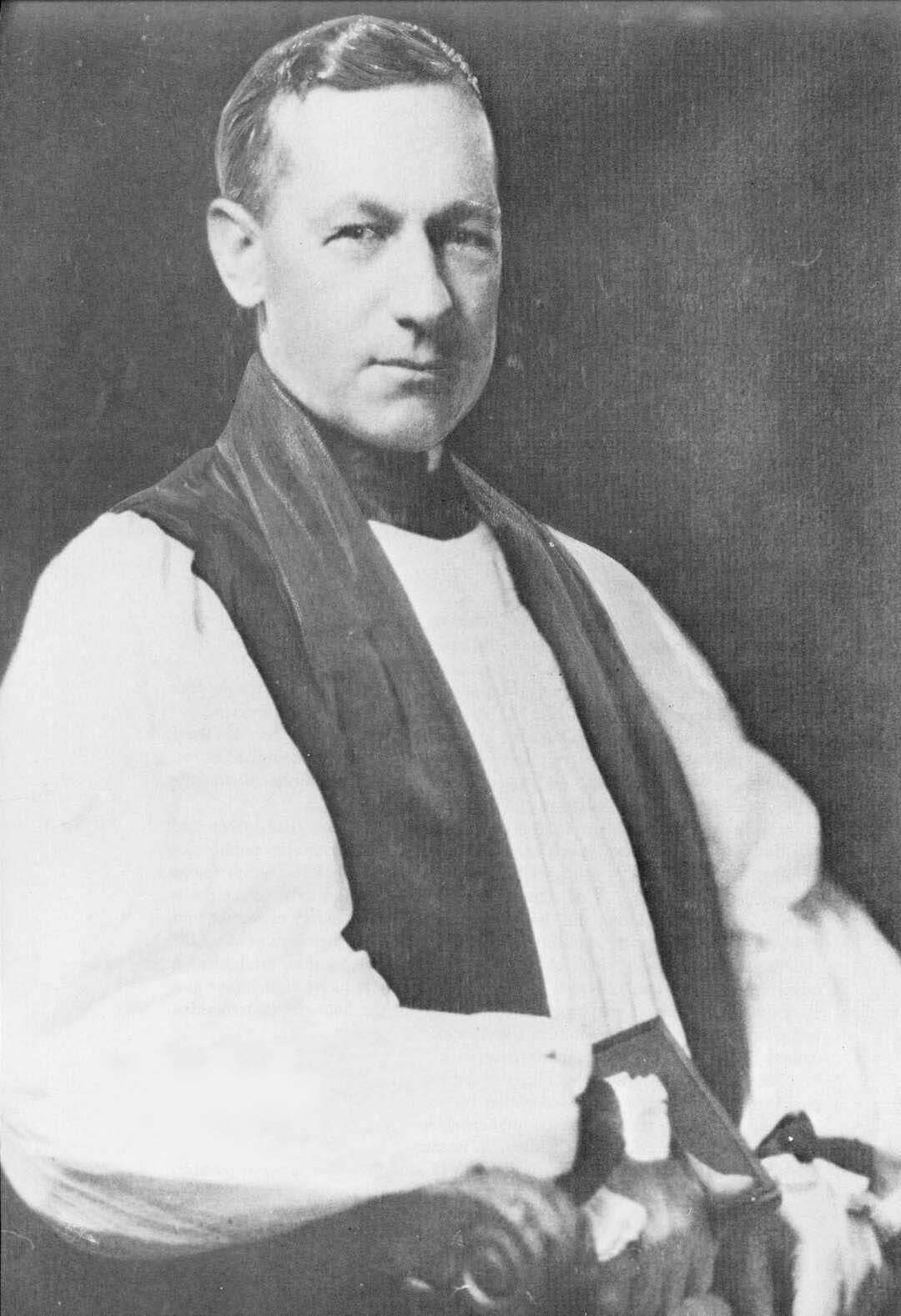

I spent some of June 18’s sermon talking about Paul Jones, Bishop of Utah from 1914 to 1917. My interest in him stems from my time as the archivist at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Salt Lake City, before I was ordained. That church had a vault about two floors below ground level, and I would wander down there on my days off and organize whatever I found. My discoveries included their vestry’s stern denunciation of the Bishop for his comments opposing the United States entry into World War I.

As I said in the sermon, Bishop Jones paid a price for his pacifist statements, even though they were directly tied to his faith in Jesus. He was forced to resign his bishopric, which had to have imposed hardships on his family. He had a wife and daughter at that time. A son would come

later. Bishop Jones moved to Brownsville Junction in Maine where he became a missionary working with railroad workers at the end of what became the Appalachian Trail.

Jones kept the faith for the rest of his life. He got involved with the Fellowship of Reconciliation, founded in 1915 to oppose the war then raging in Europe. It continues to this day, looking for nonviolent alternatives to conflict in various places in the world. Jones became its secretary for a decade. He served as interim bishop in the Diocese of Southern Ohio and was restored to the House of Bishops in 1933, though he never served as a diocesan bishop again.

He died in September of 1941, months before his country once again entered into a world war. I’ve always wondered what he thought about that. We might get some idea from his activity immediately before his death when he helped resettle Jews who had escaped the Nazis.

Jesus in June 18’s Gospel listed all the persecutions his followers could expect. Then he said that those who endure to the end will be saved. We can debate the things Jones did (our entry into the war did help bring it to a conclusion), but I think he qualifies for that end. I’m sympathetic to him in part because of my own involvement in reconciliation work.

I’m on the board of the North American chapter of the Community of the Cross of Nails. This group was founded in England after the bombing of Coventry in 1940. The cathedral was destroyed, but its dean, Richard Howard, after seeing the destruction, committed himself to a ministry of forgiveness and reconciliation. Sometime after the war ended, the community held a service of reconciliation between English and German people, and they have continued to build on that. The ruins of the destroyed cathedral remain as a sacred place next to a new cathedral committed to reconciliation. It’s a powerful symbol of the peace we can find in Christ.

The community commits itself to three guiding principles: healing the wounds of history, learning to live with difference and celebrate diversity, and building a culture of justice and peace. I suspect Bishop Jones would have approved.